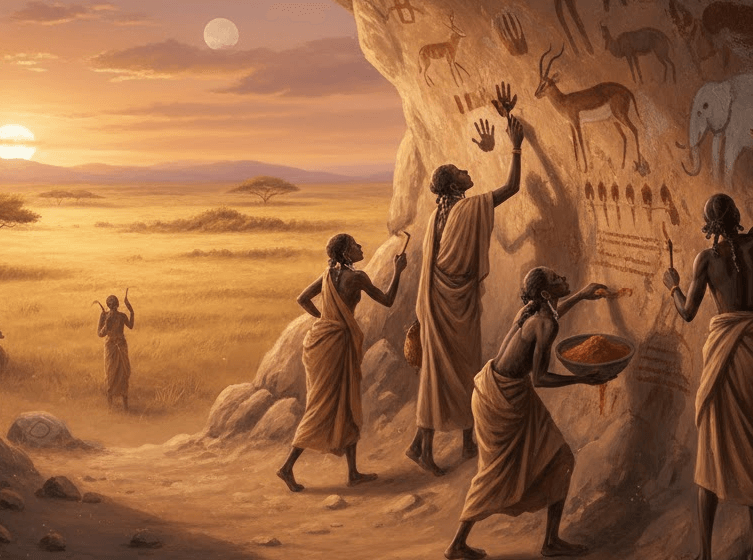

Africa: Where Paint-making Began

Source: Gemini AI

For many, the story of painting begins in Europe—deep inside limestone caves where bison gallop across stone walls and horses seem to breathe under torchlight. These images are staggering, and they rightfully occupy a central place in art history. But they are not the beginning of the story.

Long before paint adorned the caves of France and Spain, the material knowledge required to create it—selecting raw earth, grinding pigment, binding it with intention, and storing it for future use—was already an established technology in Africa. What Europe preserved at a monumental scale, Africa originated through invention.

This distinction matters. It is the difference between the location of a gallery and the origin of the medium.

The Earliest Paint-makers

The clearest archaeological evidence comes from Blombos Cave, where early Homo sapiens were producing paint nearly 100,000 years ago. Excavations revealed a complete, repeatable production line: red ochre ground into fine powder, mixed with animal bone marrow and charcoal, and stored in abalone shells.

This was not decoration by chance. It was material engineering—planned, practiced, and transmitted across generations. These early Africans were the world’s first chemists, transforming raw earth into a usable, enduring medium.

Across the continent, this knowledge expanded. From the painted stones of Apollo 11 Cave to the vast open-air galleries of Tassili n'Ajjer, African peoples developed sophisticated pigment recipes and visual languages tied to ritual and identity. Many of these works were created on exposed rock faces—environments far less forgiving than Europe’s deep, climate-stable caves.

The absence of preservation is not evidence of absence; it is evidence of a different environment.

Preservation shapes history as much as invention does.

How the Knowledge Traveled

When modern humans migrated out of Africa between 70,000 and 45,000 years ago, they did not travel empty-handed. They carried a mental toolkit: language, fire-making, and the mastery of pigments. By the time humans reached the Pyrenees, paint-making was already an ancient African legacy.

What Europe offered was not the origin of art, but the circumstance of its survival. Deep cave systems like Chauvet Cave and Lascaux Cave provided stable temperatures and humidity that allowed paintings to endure for tens of thousands of years. Over time, in the Western imagination, survival was mistaken for supremacy.

From Ancient Ochre to Master Crafts

This lineage—from African ochre workshops to European cave walls—continues into the Renaissance and into the modern day. For centuries, paint was not a commodity; it was a guarded craft. Artists selected pigments, adjusted binders, and refined preparation methods to achieve effects no one else could replicate.

Today, that same philosophy persists among master paint makers such as Michael Harding. By rejecting mass standardization in favor of high pigment loads and hand-processed oils, modern artisans mirror the material intelligence first demonstrated at Blombos. They understand that paint is not simply color—it is a relationship between earth and binder that shapes the soul and longevity of a work.

A Legacy in the Delta

When we speak of bespoke paint or mastery, we are acknowledging a truth that reaches back to Africa: paint-making is a form of deep knowledge.

For the African American community in the Northeast Louisiana Delta, this history offers a profound shift in perspective. Our ancestors did not arrive at creativity late; they authored it. From the mineral dyes used in West African textiles to the resilient Haint Blue washes found on Southern porches, the ability to transform the natural world into symbolic color is an ancestral inheritance.

Africa is where that mastery began. Europe is where it endured in stone. Understanding this restores Africa to its rightful place—not as a footnote to art history, but as its very foundation.