Interracial Collaborations That Changed Art History

When we talk about artistic innovation, we often imagine the solitary genius working alone in a studio. But many of the most important creative breakthroughs happen when two artists from completely different worlds decide to make something new together. Nowhere is that more powerful than in the collaborations between Black artists and non-Black artists—partnerships that not only produced remarkable work but expanded what art itself could be.

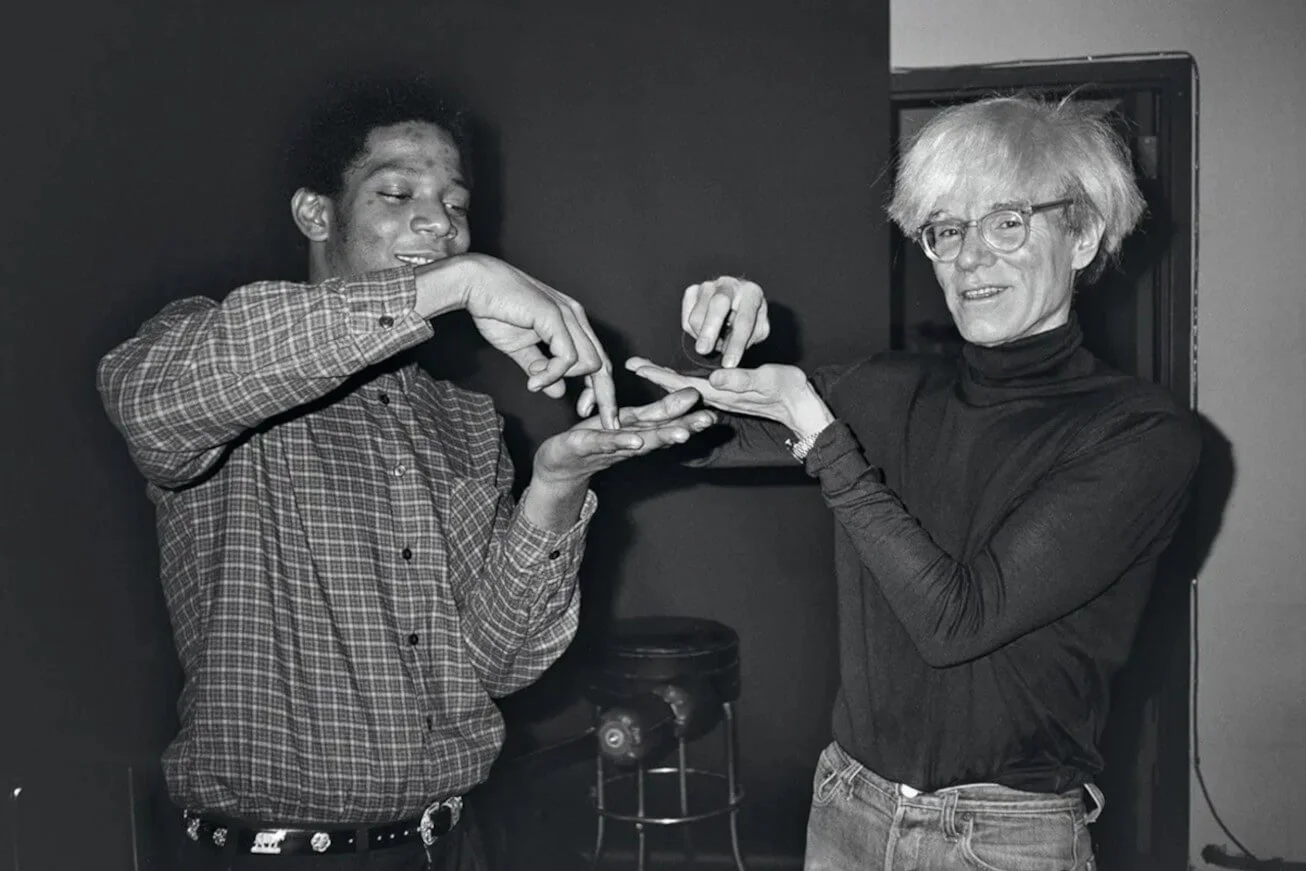

Jean Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol, (1978).

The most emblematic example is the partnership between Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol. On the surface, they had little in common. Warhol was the polished architect of Pop; Basquiat was the raw, urgent pulse of the downtown scene. Together, they created canvases that functioned as conversations—sometimes arguments—about race, celebrity, identity, and the commercialization of culture. Their collaborations feel, in retrospect, like a blueprint for the multicultural dialogues that define contemporary art today.

Kara Walker A Subtlety, Installation (2014).

Another powerful exchange can be found in the large-scale, immersive conversations between Kara Walker and Olafur Eliasson. Though they didn’t co-paint or co-sculpt in a traditional sense, their work grew in parallel and in conversation through a shared artistic language of space, scale, and experience. Walker’s monumental installation A Subtlety, created with the public arts organization Creative Time (see: What Is Creative Time?), brought historical narrative into the realm of architectural immersion. When Walker’s excavation of Black history meets Eliasson’s spatial philosophies of light and perception, the room itself becomes a story.

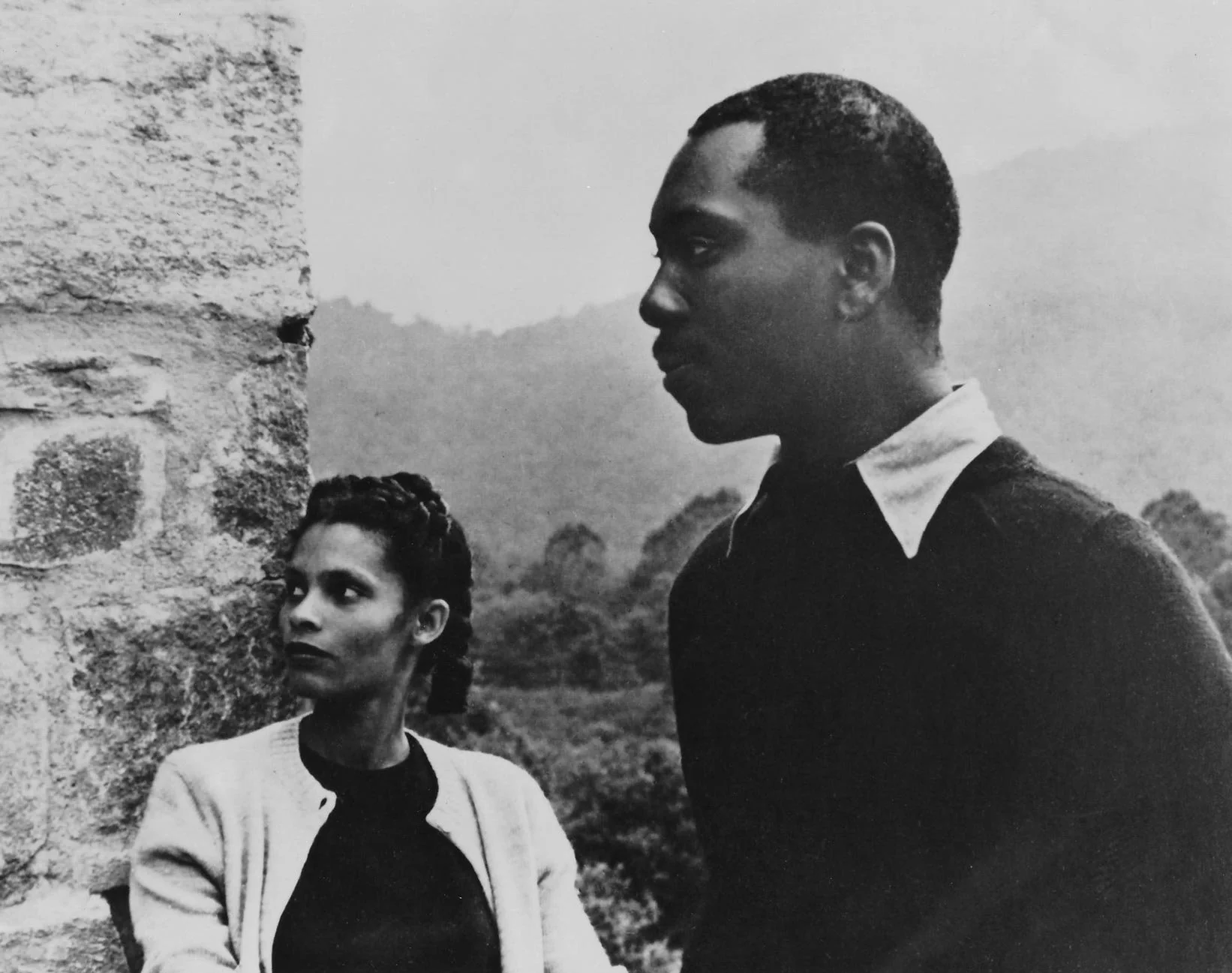

Jacob Lawrence at Black Mountain College, 1946.

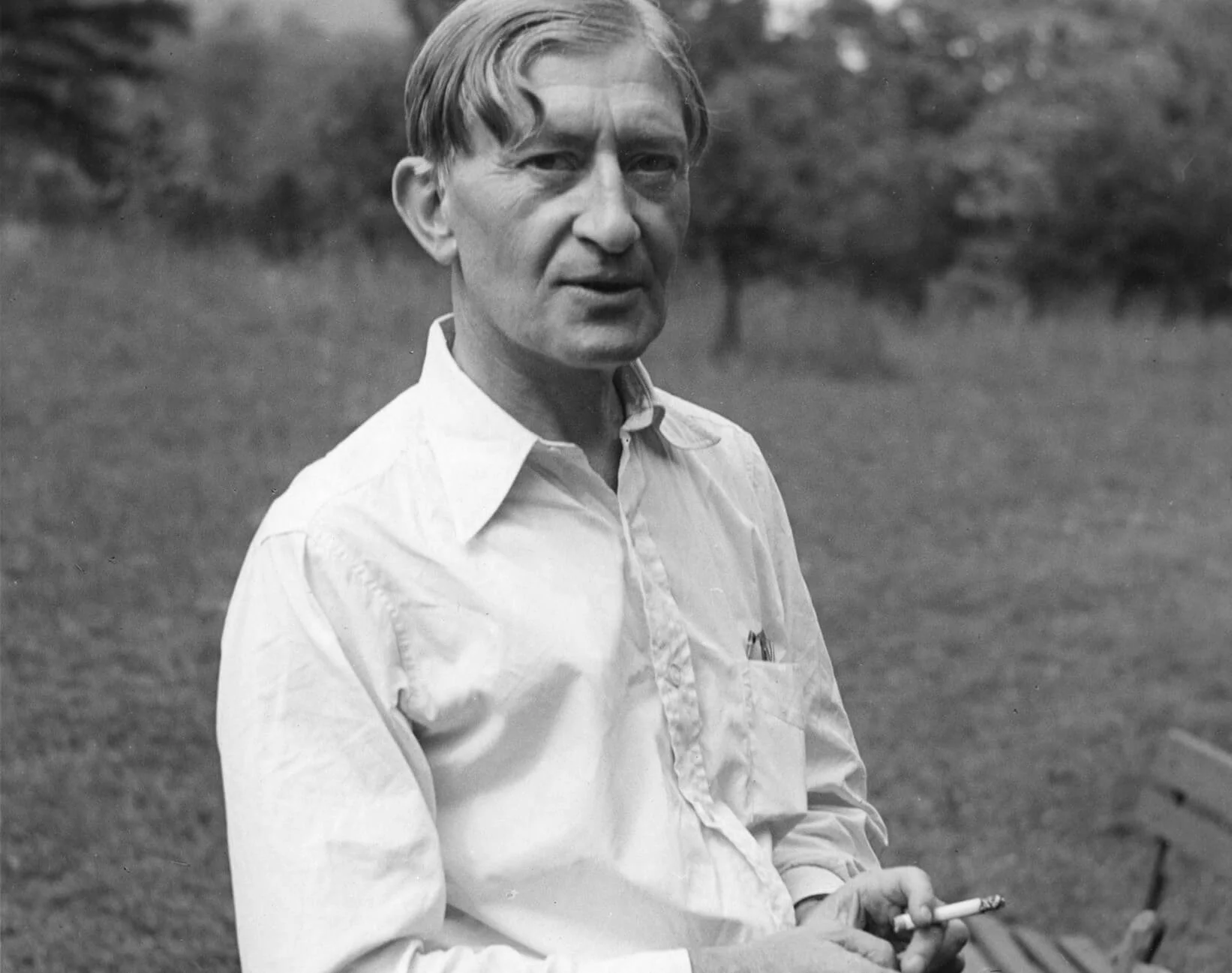

Josef Albers.

A third collaboration reaches back to the mid-twentieth century at Black Mountain College, where Jacob Lawrence worked alongside Josef Albers, one of the great figures of the Bauhaus (see: What Was the Bauhaus?). Lawrence was already established when he arrived, but the conversations he had with Albers (see: Who Was Josef Albers?) sharpened his structural instincts and created a rare space for racially integrated artistic exchange during an era when segregation was still a reality across the country. This was collaboration not of co-signatures but of ideas, and it helped shape the foundation of American modernism.

These collaborations remind us that culture is built in moments of meeting. When artists cross lines—racial, cultural, aesthetic—they expand what is possible. They allow the work to carry multiple histories at once. And they show us that creativity is strongest when no one owns the conversation and everyone reshapes it.

In a time when we are still asking how stories get told and who gets to tell them, these partnerships offer a kind of map. They reveal not just what art can look like, but how art can connect us—across difference, across experience, and across the shifting landscapes of history itself.