The Radical Vision of Black Conceptual Artists

Marcel Duchamp's Fountain, (1917). Conceptual art.

The Conceptual Art movement took hold in the 1960s and was founded on a powerful, often overlooked idea: that the concept behind a work of art could matter more than the physical object itself. This was a radical shift in a time when craftsmanship and the artist’s visible skill were still considered the primary measures of value.

Marcel Duchamp had paved the way decades earlier through his “readymades,” ordinary objects he declared to be art. His most famous example, Fountain (1917)—a standard urinal signed “R. Mutt”—posed a simple but provocative question: if an artist says something is art, what makes it not?

Building on this, Sol LeWitt formalized the philosophy. Through his instruction-based wall drawings, he demonstrated that an artwork could be executed by anyone as long as the originating idea remained intact. For LeWitt, the concept itself was the artwork.

Joseph Kosuth pushed the movement even further into the realm of language. Works like One and Three Chairs asked viewers to decide which representation—an object, a photograph, or a definition—truly embodied the art.

Together, these artists established a cool, analytical, and often philosophical language for Conceptual Art.

Black Artists Redefine the Concept

While the mainstream art world celebrated the philosophical inquiries of these white figures, a generation of Black artists was using those very same conceptual strategies—language, systems, readymades, and performance—to probe urgent questions of identity, power, and institutional racism.

These artists were prolific and critically engaged throughout the 1960s and 70s, yet their work was largely absent from the emerging conceptual canon. This absence grew out of two conflicting forces:

Structural Racism: Predominantly white institutions frequently overlooked or minimized Black conceptualists regardless of their rigor or innovation.

Aesthetic Tensions: Within the broader Black Arts Movement, figurative and explicitly political imagery often took precedence. Conceptual abstraction, though deeply political, was sometimes dismissed as too “detached,” creating an internal divide over what Black art should be.

In response, Black conceptualists shaped their own experimental ecosystem—most notably the groundbreaking Just Above Midtown (JAM) gallery in New York. JAM became an incubator for radical ideas, a place where conceptual strategies could unfold through the lens of the Black experience, imagination, and critique.

Here are five of the most influential figures in Black Conceptual Art:

Adrian Piper: Making Perception Political

Adrian Piper.

Piper began her career closely aligned with the formalism of LeWitt before recognizing that her identity as a Black woman inevitably shaped and politicized how her art was seen and interpreted. Her goal became making the viewer's gaze part of the art.

Adrian Piper, The Mythic Being, (1973).

Key Work: The Mythic Being (1973). Piper transformed herself into a fictional working-class Black male, performing mundane actions in public while reciting philosophical diary entries. The confrontation she provoked—curiosity, discomfort, and avoidance—became the final conceptual layer of the piece.

David Hammons: Grounding the Readymade in Social Critique

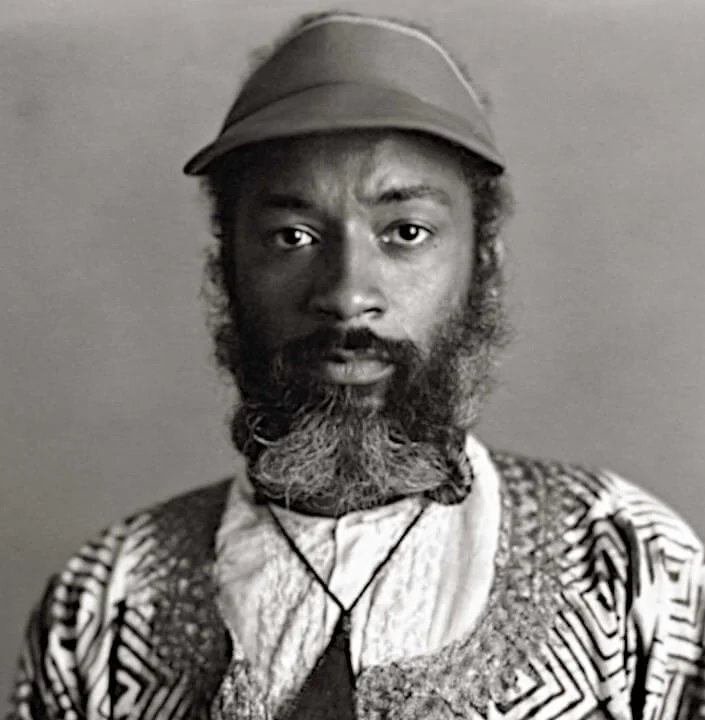

David Hammons.

David Hammons took Duchamp’s idea of the Readymade and grounded it in the materials and symbols of Black urban life. Hair swept from barbershop floors, discarded wine bottles, chicken bones, and grease became the raw substance of his critique of both American society and the art world’s elitism.

David Hammons, Bliz-aard Ball Sale, Cooper Square, New York, (1983).

Key Work: Bliz-aard Ball Sale (1983). Hammons stood on a Manhattan sidewalk selling snowballs arranged by size. This sharp, simple street gesture transformed the concept of commerce into a direct question: what determines an object’s value, and who has the authority to decide?

Charles Gaines: Revealing Subjectivity in Systems

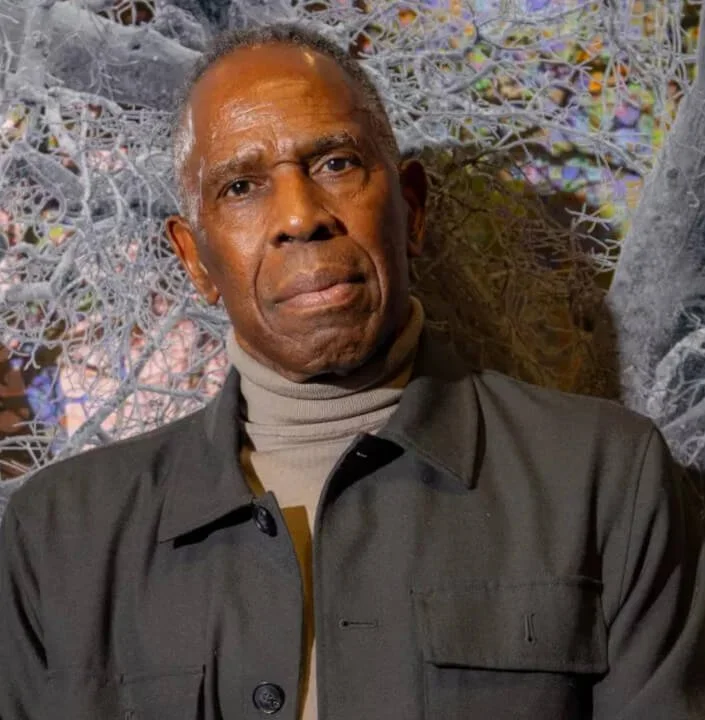

Charles Gaines.

Gaines turned to the mathematical logic associated with conceptual art while revealing the subjectivity embedded within those very structures. He proved that systems are not neutral; they are a framework we impose on the world.

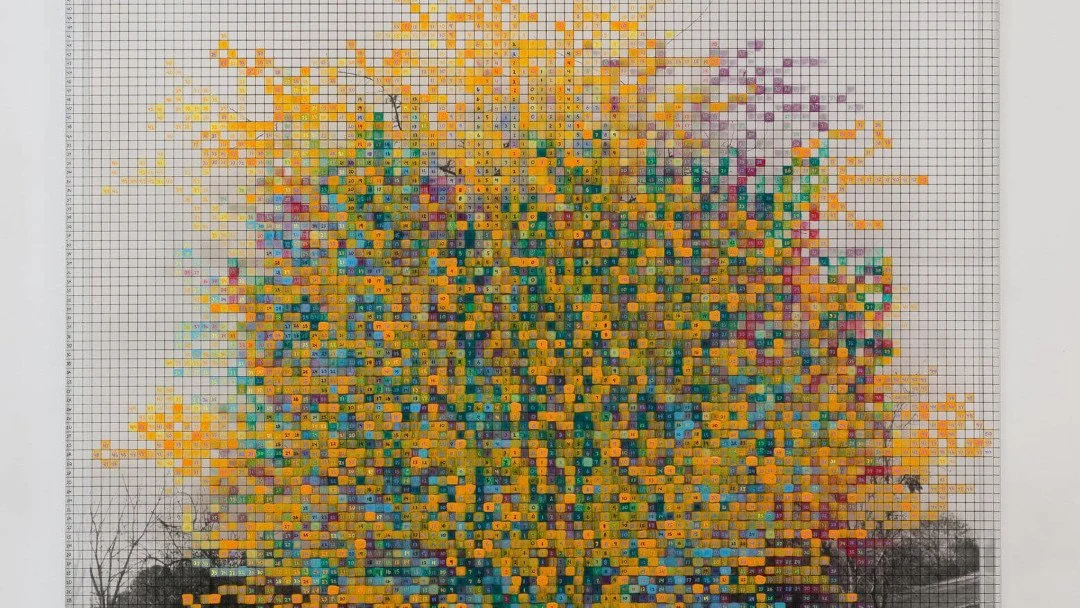

Charles Gaines, Numbers and Trees V, Landscape #8: Orange Crow, (1989).

Key Work: His Gridwork series. Photographs of organic forms (like trees and faces) were meticulously translated into numbered grids. This work anticipated the digital age’s reliance on data and classification, demonstrating that even the most "neutral" systems carry assumptions about organization and hierarchy.

Senga Nengudi: The Poetics of the Body

Senga Nengudi.

Nengudi approached conceptualism through performance, the body, and the poetics of everyday materials. Her practice grounds abstract ideas in visceral physicality.

Senga Nengudi R.S.V.P. (1977). Sculpture activated by Maren Hassinger.

Key Work: The long-running R.S.V.P. series (first created in the 1970s). These pieces use stretched and knotted pantyhose filled with sand to evoke the physical strain, resilience, and vulnerability of the human form , especially women’s bodies shaped by childbirth, labor, and societal expectation.

Pope.L: Enduring the Invisible

Pope.L.

Pope.L carried conceptualism into the realm of endurance, absurdity, and public confrontation to highlight the realities of poverty and the invisibility of marginalized people.

Pope.L. The Great White Way (2001–2009).

Key Work: The Great White Way (2001–2009). He crawled the entire 22-mile length of Broadway in Manhattan over several years. This grueling journey operated as a “long sculpture” made of time, pain, and physical exertion, forcing viewers to confront the social hierarchies that determine whose labor and whose bodies are seen, ignored, or forgotten.

Taken together, these artists reveal that the conceptual revolution was more diverse, more socially engaged, and more politically charged than the traditional narrative exposed. By bringing their contributions into focus, we at the Northeast Louisiana Delta African-American Heritage Museum encourage you to explore a more complete and comprehensive history of conceptual art.