Artist Spotlight: Bill Traylor

From Benton Fields to the Heart of American Art

Bill Traylor (c. 1853–1949) lived a life that charts a remarkable arc through American history. Born into slavery on a plantation in Benton, Alabama, he spent most of his life working the land, first as an enslaved laborer and later as a sharecropper. This makes his artistic career all the more extraordinary: beginning to draw in his mid-eighties, Traylor created a body of work that would ultimately reshape our understanding of American art.

A Late Start, a Lifelong Vision

In the late 1930s, Traylor moved to Montgomery, Alabama. Elderly and with no permanent home, he took a seat on Monroe Street and began to draw on whatever materials were at hand—discarded cardboard, scraps of paper—using a limited palette of pencil, ink, and poster paint. Between 1939 and 1942, he produced more than 1,200 works—an astonishing outpouring of creativity for any artist, let alone one beginning so late in life.

These drawings were not the product of formal training but a direct visualization of a lifetime of memory and observation. They synthesize the rural world of his past with the dynamic, modern urban environment of Montgomery.

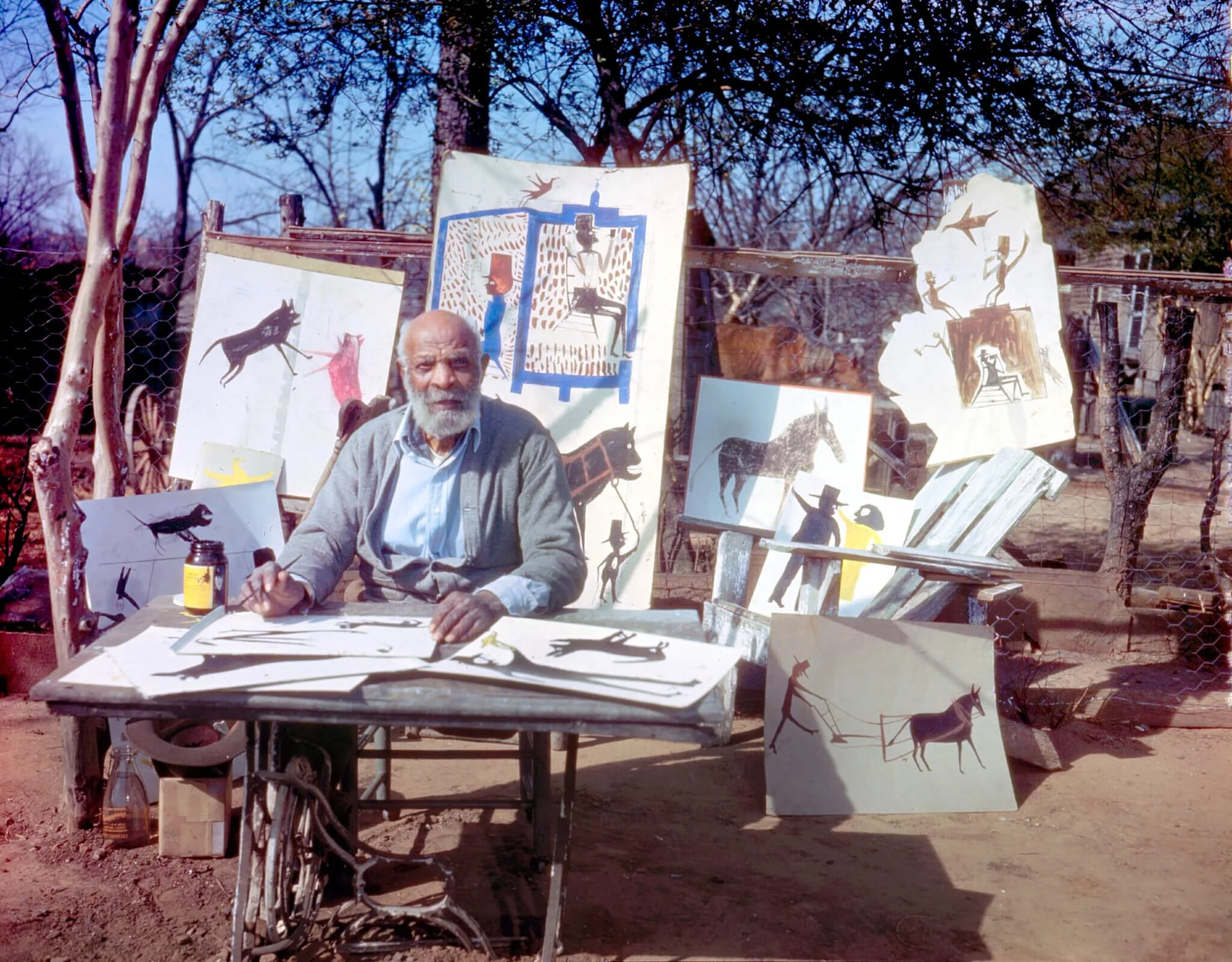

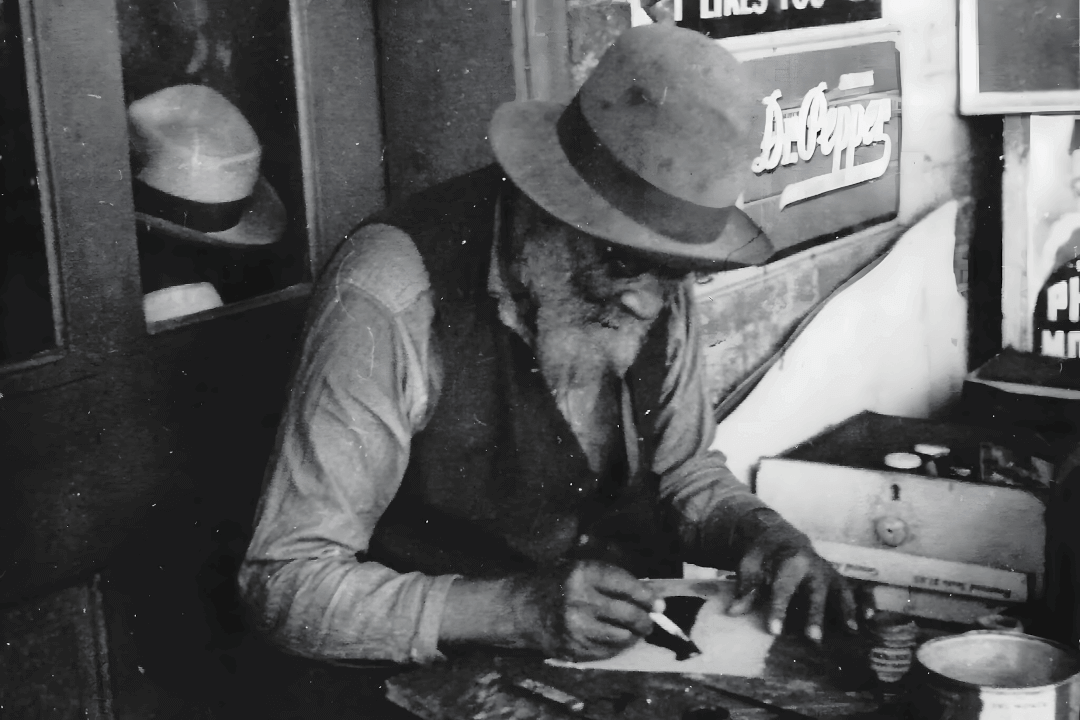

Bill Traylor at work on Monroe Street.

A Distinct Visual Language

Traylor’s work is immediately recognizable for its graphic power and economy of form. He frequently used bold silhouettes and flattened perspectives to depict a world of figures, animals, and scenes both mundane and mysterious. His recurring motifs—men in top hats, struggling animals, dancing figures, and geometric patterns—form a vivid visual narrative of Black life in the post-Reconstruction South.

Art historians analyze these images as a form of visual storytelling rich with allegory. Scenes of conflict and balance, for instance, can be read as commentaries on social tension, spiritual resilience, and the quest for freedom.

“Blue Cat” by Bill Traylor.

While his work is often categorized under “folk” or “outsider art,” its sophisticated composition and rhythmic balance have also drawn comparisons to modernist abstraction, positioning Traylor as a unique figure bridging multiple artistic traditions.

Recognition and Legacy

Traylor’s genius was first recognized by a younger artist, Charles Shannon, who encountered him on Monroe Street in 1939. Shannon provided materials, collected Traylor’s work, and became his first champion. Widespread acclaim, however, came decades later. Today, Traylor is celebrated as one of the most significant self-taught artists of the 20th century, with his work residing in the permanent collections of institutions such as the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Bill Traylor’s work on display at the American Folk Art Museum. Photo: Suzanne DeChillo/The New York Times.

His legacy challenges the conventional boundaries of art history, reminding us that profound creative expression can emerge from any circumstance. Through his drawings, Traylor preserved memory, identity, and the enduring spirit of human imagination.

This post is part of the Northeast Louisiana Delta African American Heritage Museum’s Artist Spotlight series, highlighting visionary artists whose work deepens our understanding of African American art and cultural history.