The Unseen Hands: Black Artists Who Shaped U.S. Currency

We carry their work in our pockets. We fold it into birthday cards, tuck it into offering plates, or pass it to strangers at gas stations. But how often do we think about the artists behind the images on our money?

While the faces on coins and bills may be historic, the designs themselves are the work of living hands—engravers, sculptors, and artists who shape national memory through form. Among these creators are several Black artists whose contributions to U.S. currency design remain both powerful and underrecognized.

Isaac Scott Hathaway – Sculptor of Legacy

Isaac Scott Hathaway

In 1946, Isaac Scott Hathaway became the first African American artist to design a U.S. coin. He was the designer behind the Booker T. Washington commemorative half dollar—followed by the George Washington Carver–Booker T. Washington half dollar, issued between 1951 and 1954. These were not coins of wide circulation; rather, they were commemorative, produced in limited quantities and sold primarily to collectors. Still, they represented a quiet but meaningful breakthrough in national symbolism.

Washington-Carver commemorative half dollar, 1952.

Hathaway was a classically trained sculptor and educator. In addition to his work with the U.S. Mint, he designed more than 100 portrait busts of notable African Americans and sculpted the bust of George Washington Carver now housed at Tuskegee University. His work placed Black historical figures into the material record at a time when very few institutions were willing to do so.

Brian Thompson – Engraving the New Era

Designer Brian Thompson poses with his banknote.

Brian Thompson holds the distinction of being the first African American artist to contribute to modern U.S. paper currency. Working as an engraver for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP), Thompson helped design the 1996-series redesigns of the $50 and $100 bills—part of a broader anti-counterfeiting initiative that introduced color-shifting ink, watermarks, and new layout elements.

While currency design is highly collaborative and attribution is often shared across departments, Thompson’s presence in these efforts marked a significant step toward diversifying the artistic teams shaping national imagery. His contributions reveal that currency is not fixed or neutral—it is a cultural artifact, shaped by human choices and, increasingly, by whose labor we choose to recognize.

Ed Dwight – Correcting the Historical Record

Ed Dwight

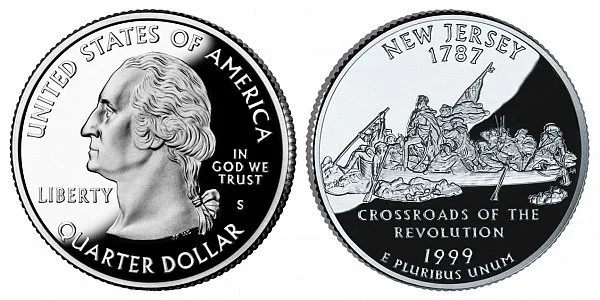

In 1999, sculptor Ed Dwight—renowned for his public monuments of Black historical figures—entered the world of coin design. He created the reverse of the New Jersey State Quarter, part of the U.S. Mint’s 50 State Quarters program. His design famously depicts George Washington crossing the Delaware—but with a vital difference: Dwight’s version includes a Black soldier in the boat, a visual correction of a long-erased truth.

New Jersey Statehood Quarter.

Though some historians debate whether Crispus Attucks or other Black patriots were present during that specific crossing, the intent behind Dwight’s inclusion is historically sound: Black soldiers fought and died in the Revolutionary War, and their absence from official imagery is part of a broader pattern of erasure.

Dwight’s work on the quarter wasn’t just historical—it was corrective.

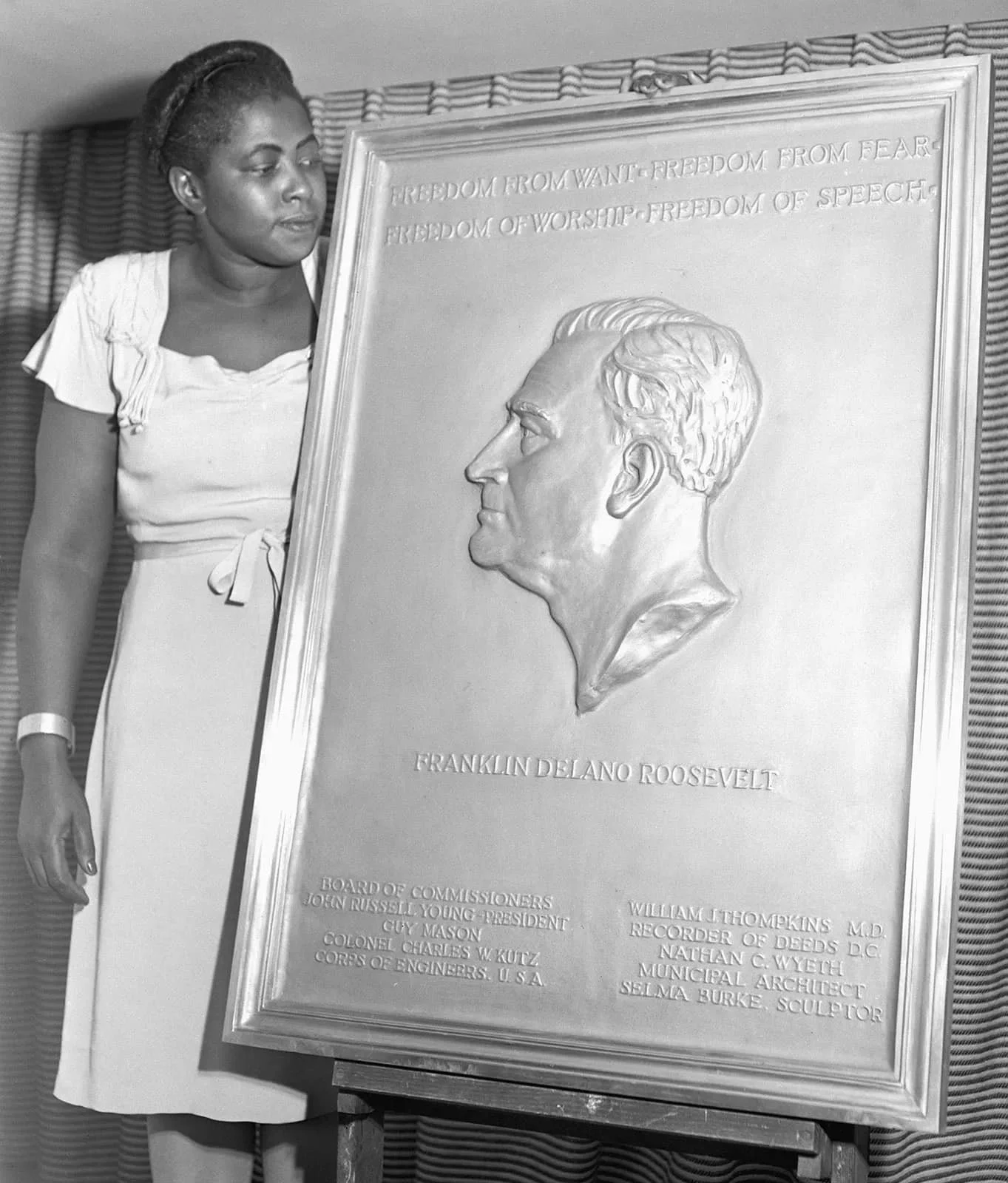

Selma Burke – The Portrait Behind the Dime

Selma Burke with her bronze relief portrait of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 1943.

Though she was never officially credited, sculptor Selma Burke’s portrait of Franklin D. Roosevelt is widely understood to have inspired the image that appears on the U.S. dime. Burke, a Harlem Renaissance artist and teacher, created a relief of FDR in 1944 based on a live sitting. When the dime was released the following year, it bore a striking resemblance.

Though the Mint credited white engraver John R. Sinnock, Burke's influence has been acknowledged by historians and Roosevelt himself. Her case reminds us that Black artists have shaped American iconography—even when their names were left off the credits.

Why It Matters

Currency is more than commerce. It’s narrative. It tells us who we value, what we honor, and how we define legacy. The contributions of Black artists to U.S. currency—whether etched in metal, pressed in ink, or buried beneath layers of bureaucratic anonymity—reveal just how much of American culture is shaped by unseen hands.

These artists paved the way for modern efforts to diversify the face of money itself—including the proposal to place Harriet Tubman on the $20 bill, a plan announced in 2016 and then indefinitely delayed under a subsequent administration. Even currency design remains subject to politics, power, and resistance.

At our museum, we believe that the objects we handle every day deserve scrutiny, reflection, and recognition. That includes what we carry in our wallets.

Next time you hold a coin or bill, look closer. Someone designed that. And someone—maybe someone you’ve never heard of—fought to be seen in it.