Black Art Films: Why They Matter

At the Northeast Louisiana Delta African American Heritage Museum, we celebrate Black artistry in all its forms—from the quilts of Gee’s Bend to the blues of the Mississippi Delta. Film, too, is a canvas. And just as our exhibitions preserve memory through fabric and song, Black art films preserve it through light and motion. These films are not only cinematic experiences—they are cultural artifacts, expressions of Black interiority, and bold declarations of artistic sovereignty.

Reframing the Frame: A Historical Perspective

Traditionally, the term "art film" has been associated with European cinema—think Bergman, Fellini, or Tarkovsky. These directors are praised for creating films that prioritize mood over plot, symbolism over spectacle. Their work is often slow, meditative, and unapologetically ambiguous, asking viewers not just to watch, but to "contemplate".

However, the history of art film—like so many art histories—has largely overlooked Black voices. While white auteurs explored existentialism and alienation, Black filmmakers were battling for access, funding, and representation. Yet within this struggle, something transformative occurred: Black artists didn’t merely adopt the art film form—they redefined it.

Black art films carry the contemplative spirit of global art cinema but ground it in lived realities: ancestry, displacement, spiritual inheritance, and cultural memory. They reject spectacle in favor of reverence. They speak in the language of ritual, family, and resistance—often shaped by the South’s unique cadence and pain.

Charles Burnett’s "To Sleep with Anger" (1990)

Charles Barnett, dir. To Sleep with Anger.

A key example is Charles Burnett’s "To Sleep with Anger". Set in South Central Los Angeles, it tells the story of a Black family visited by a mysterious figure from their past. But beneath its domestic drama lies a mythic Southern subtext—one that resonates with the folk traditions and spiritual tension found in rural Black Southern life.

Danny Glover’s Harry feels less like a character than a force of nature—an ancestral disruption. Burnett, a founding figure of the L.A. Rebellion movement, resists conventional storytelling to dwell in stillness, silence, and unresolved tension.

Danny Glover and Julius Harris, To Sleep with Anger.

The L.A. Rebellion was a group of Black filmmakers trained at UCLA during the 1970s and 1980s who rejected Hollywood's formulas and stereotypes. Influenced by Third Cinema and Italian neorealism, they created independent films that centered Black life as complex, interior, and often unspoken. Their work—including Haile Gerima’s "Sankofa" and Billy Woodberry’s "Bless Their Little Hearts"—formed a cinematic revolution rooted in Black experience, cultural integrity, and political clarity.

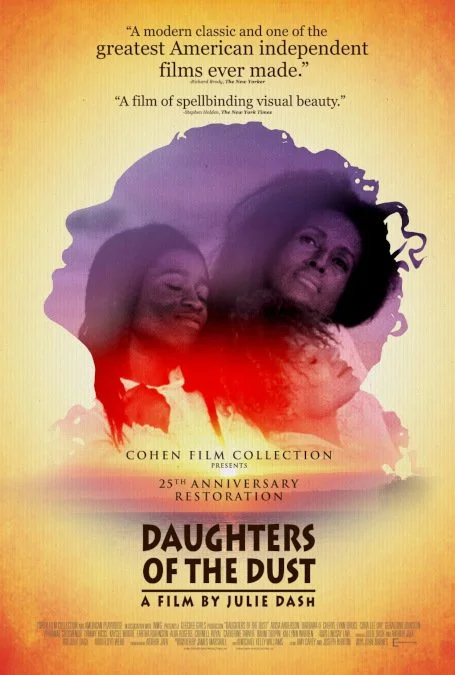

Julie Dash’s "Daughters of the Dust" (1991)

Julie Dash, dir. Daughters of the Dust.

Julie Dash’s "Daughters of the Dust" is one of the most celebrated Black art films of all time. The first widely distributed feature by a Black woman director, it tells the story of Gullah women preparing to leave their Sea Island home in 1902. With dreamlike visuals and poetic narration, Dash captures a moment of transition, both personal and historical.

The film’s aesthetic brilliance owes in part to internationally acclaimed visual artist Kerry James Marshall, who served as its production designer. Marshall brought a fine artist’s eye to the film’s visual composition—each frame rich in symbolism, shadow, and color.

Dash’s film immerses us in Gullah culture, a sister to Louisiana’s Creole traditions. Like our own Delta stories, it carries the weight of ancestry in every frame. The past is not distant, but tactile, luminous, and alive.

Khalik Allah’s "Black Mother" (2018)

Khalik Allah, dir. Black Mother.

In the contemporary realm, Khalik Allah’s "Black Mother" stands as a radical meditation on Black womanhood, Jamaican identity, and spiritual endurance. Shot with handheld cameras and layered audio, the film eschews traditional narrative to offer something more intimate: a visual and sonic tapestry that feels more like a prayer than a plot.

Allah’s approach—lingering portraits, overlapping voices, rhythmic edits—echoes both the avant-garde and African diasporic oral traditions. His work embodies the spiritual and aesthetic lineage of Black art films: rooted, reverent, resistant.

What Sets Black Art Films Apart?

Black art films differ from both traditional art cinema and mainstream studio films in their intentional cultural grounding. These are not universalized, symbolic parables. They are regionally specific. They carry dialects, memories, migrations. They echo sermons, lullabies, and spirituals.

Where studio films chase climax and closure, Black art films often reject tidy resolution. They honor the sacredness of silence and the beauty of unresolved memory. Their pacing mimics ritual. Their narratives are cyclical, not linear—because history repeats, and healing is nonlinear.

Why These Films Matter to Us

At our museum, we see these films as kindred works—part of the same continuum that gives us quilts, carvings, gospel, and poetry. They tell stories that feel familiar to our region: of families torn and restored, of cultural survival, of spirituality rooted in soil.

Would you like to see screenings of Black art films at the museum? We’d love to know which of these stories resonates with your own. Let us hear from you.

Film is not just film. It is art. And in the hands of Black creators, it becomes a sacred tool for remembering who we are—and imagining who we might yet become. Come visit, reflect, and share.