Who is the Most Famous Black Artist/Painter in History?

If we’re talking about cultural saturation, market visibility, and lasting influence, Jean‑Michel Basquiat is arguably the most famous Black painter in modern history.

His rise in the early 1980s—out of downtown New York and into the global canon—combined a new visual grammar (text spliced into image, anatomy next to heraldic crowns, history colliding with street signage) with an unblinking critique of race, power, and representation. In 2017, his Untitled (1982) set a record for the artist at $110.5 million—a price that also cemented his public myth as much as his market stature.

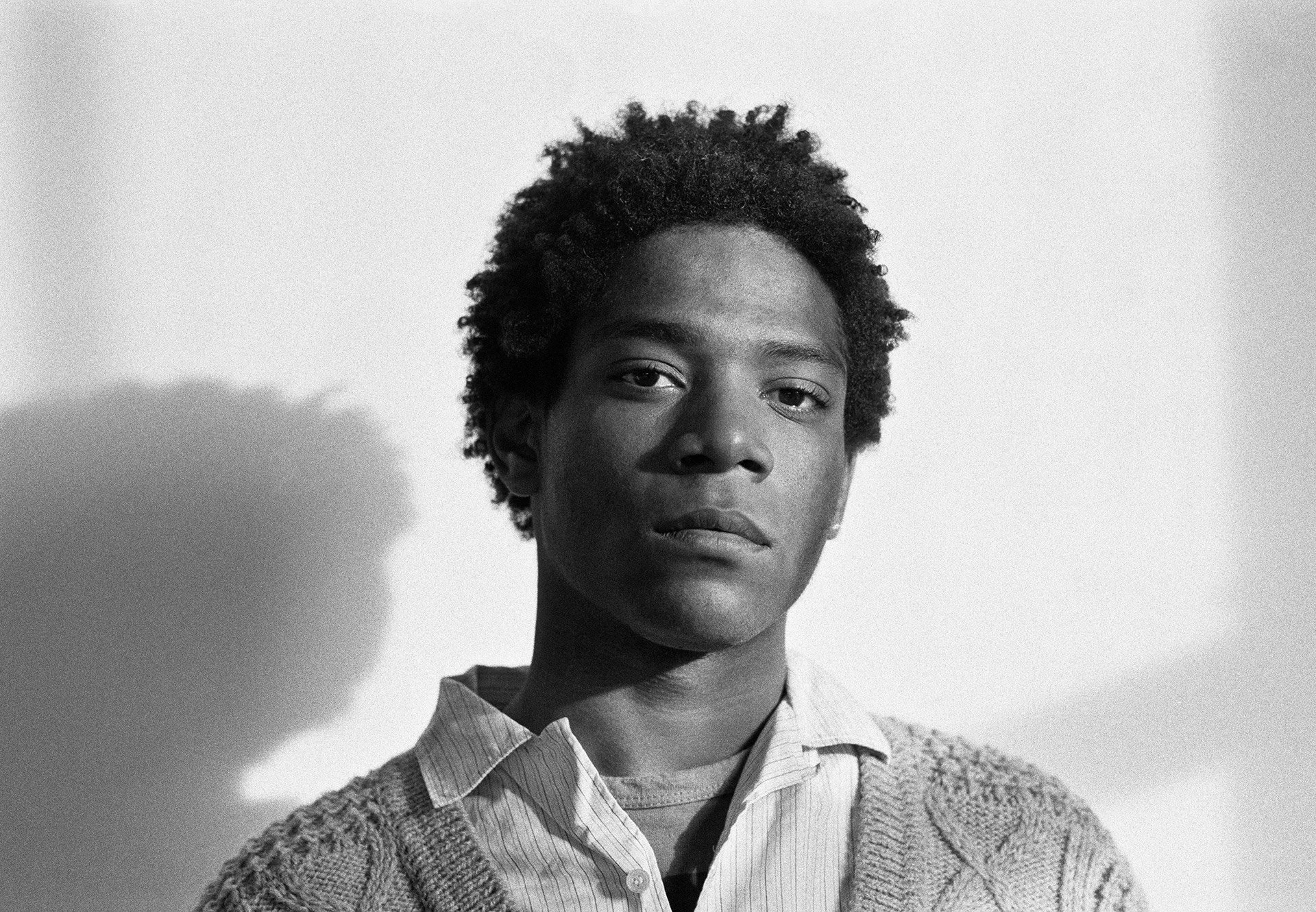

Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1984 Photograph by Lee Jaffe, Copyright, All Rights Reserved Courtesy of LW Archives

Why Basquiat’s Fame Matters (and How It Was Built)

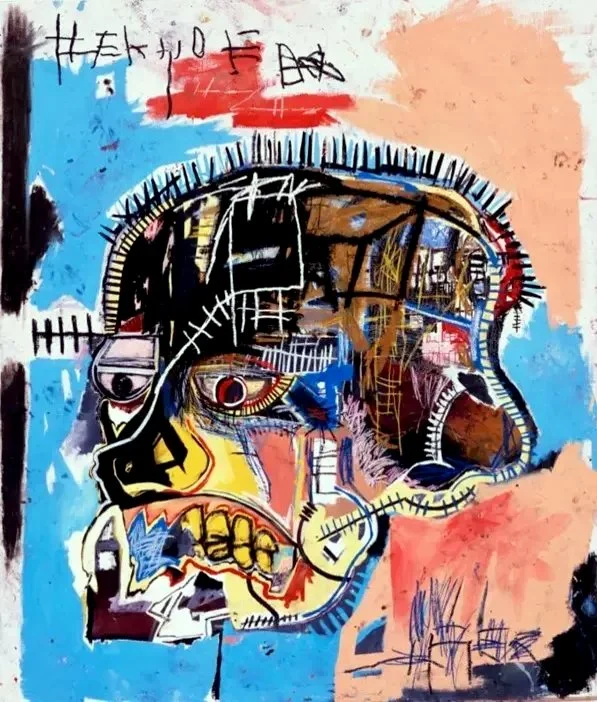

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Head), 1981. Acrylic and oilstick on canvas mounted on wood supports.

Basquiat’s work still feels contemporary because it merges urgency with complexity: the canvases are legible at a glance yet dense with references, from anatomical diagrams to jazz. But fame isn’t generated by style alone. Patronage, institutional access, and timing shaped his ascent. Early backing from dealers like Annina Nosei and Larry Gagosian, international validation at Documenta 7 (where at 21 he was the youngest participant), and a polarizing collaboration with Andy Warhol all amplified his visibility—sometimes productively, sometimes contentiously. Recognizing those networks doesn’t diminish the work; it clarifies the ecosystem through which it circulated.

He Didn’t Emerge in a Vacuum

To say Basquiat “arrived” is to risk erasing the artists who prepared the ground he sprinted across.

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Banjo Lesson, 1893, oil on canvas, 124.5 × 90.2 cm (Hampton University Museum, Hampton, VA)

Henry Ossawa Tanner achieved international recognition in the 1890s; his The Banjo Lesson (1893) countered minstrel caricature with intimate humanism.

Jacob Lawrence transformed modernist economy into narrative power; The Migration Series (1940–41) distilled a defining American story into 60 panels of crystalline clarity.

Placing Basquiat in this lineage resists a “great man” arc. He carried the baton—he didn’t invent the race.

The Debate Is Useful

Is Basquiat the consensus answer? Many would still say yes, particularly when “fame” is measured by name recognition across art, music, and fashion. Others might argue for artists whose public reach hinged on monumental visibility or civic symbolism—Kara Walker (silhouette installations), Kehinde Wiley (the Obama portrait), or Faith Ringgold (story quilts). Acknowledging that dissent doesn’t weaken the claim; it situates the question inside living culture rather than a settled canon.

Influence That Keeps Moving

Basquiat’s visual vocabulary—crowns, skeletal heads, crossed‑out words—remains a lingua franca for artists and designers. But the most meaningful influence is conceptual: a license to tell Black histories at scale and in the present tense. Contemporary painters like Kerry James Marshall and Julie Mehretu extend that project differently—Marshall by installing Black life at the center of history painting, Mehretu by mapping power, place, and time through abstraction. The continuum matters as much as the peak.

What Museums Do With This Answer

Calling Basquiat the most famous Black painter isn’t just about auction highs; it’s about what his work makes visible: the unfinished work of representation and the infrastructures that enable (or obstruct) an artist’s rise. At the Northeast Louisiana Delta African‑American Heritage Museum, we recognize that visibility as a responsibility. We make every effort to link local histories to global ones, and to honor the breadth of Black artistic achievement from Tanner and Lawrence to Marshall, Mehretu, and beyond.

Your turn:

Who would you name as the most famous Black artist in history—and why? Tell us what “fame” should measure. We’ll feature thoughtful responses in a future post.