The Evolving Face of Jesus: From Symbol to Self

From Roman Catacombs to African and African-American Reinterpretations

Conventional histories of Christian art tend to follow a single path leading from Roman catacombs through the great European cathedrals. This narrow focus has consistently overlooked a much broader and richer story. A full understanding requires examining not just the European development of Christian imagery but also the powerful and enduring visual traditions that flourished in Africa. Furthermore, we must acknowledge how the African diaspora, having a foreign iconography imposed upon them, undertook the profound theological work of recreating the divine in their own likeness.

Early Christian Symbols

Ichthys was adopted as a Christian symbol.

The European journey toward a standardized image of Christ is documented through specific artifacts. Early Christians, living under persecution, expressed their faith through a symbolic language rather than figurative art. Archaeological digs at sites like Rome’s Catacombs of Domitilla have uncovered widespread use of the Ichthys, a fish symbol serving as an acronym for "Jesus Christ, God’s Son, Savior."

The Chi-Rho (☧) symbol is a monogram formed from the first two letters of the Greek word Χριστός (Christos), meaning “Christ.”

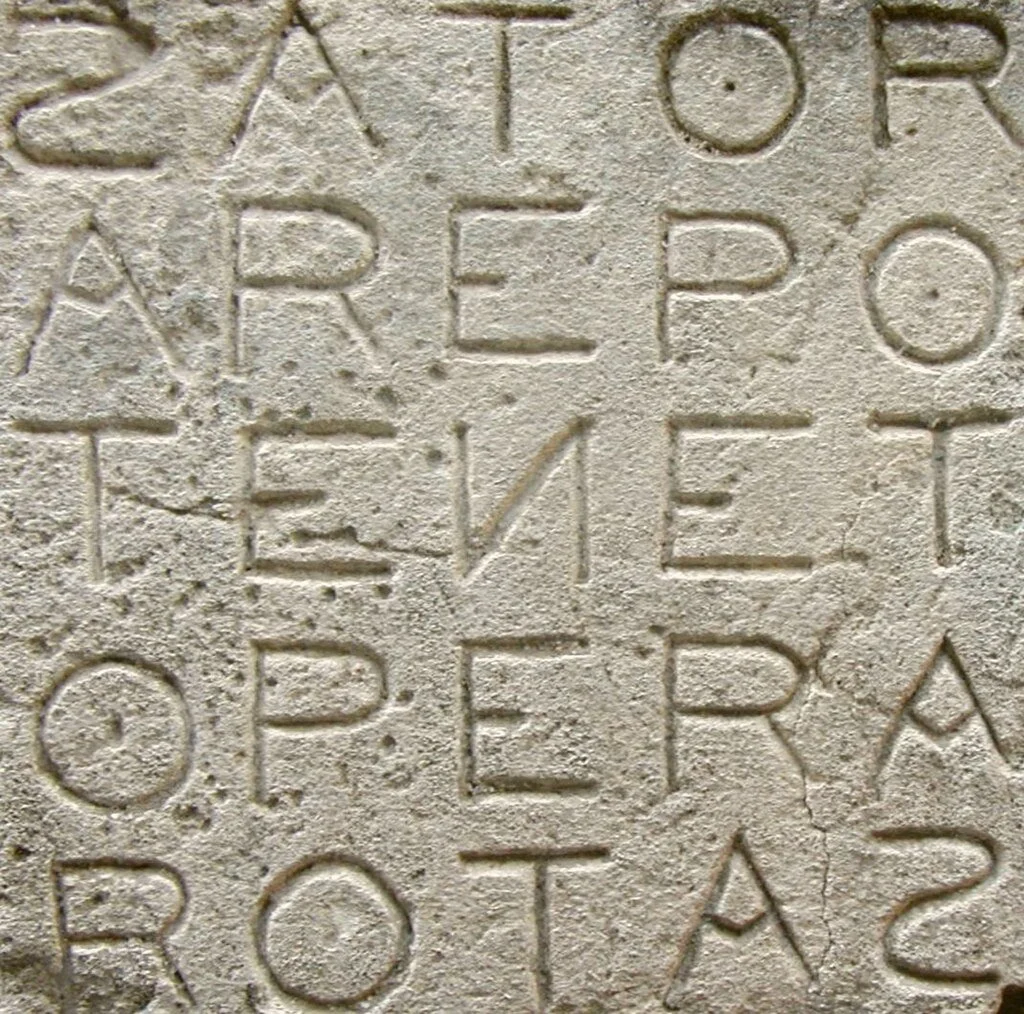

Sator Square etched onto a wall in the medieval fortress town of Oppède-le-Vieux, France.

They also employed the Anchor as a disguised cross and the Chi-Rho monogram. A more complex example is the Sator Square, a palindromic word puzzle found on walls from Pompeii to Cirencester, England, which scholars like Duncan Fishwick have shown conceals a cross formation spelling "PATER NOSTER" and the Alpha and Omega.

The European Image of Christ

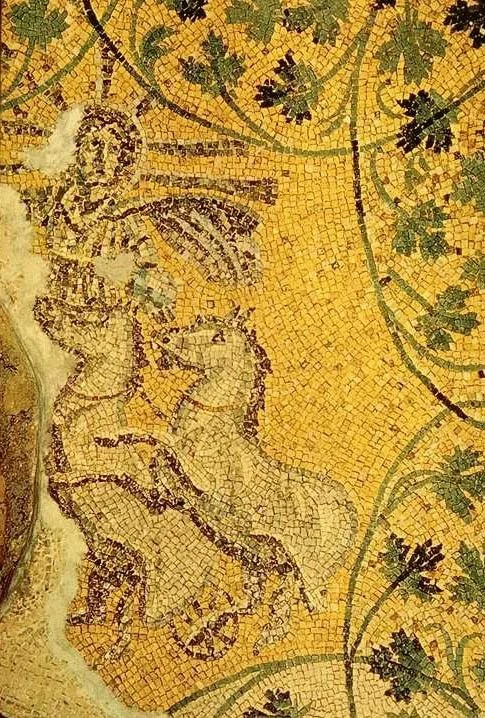

Mosaic of the 3rd century on the Tomb of the Julii under St. Peter's Basilica.

As Christianity gained legal status, its artists began creating human images of Christ by adapting familiar pagan models. A third-century mosaic in the Mausoleum of the Julii beneath St. Peter’s Basilica depicts Christ as Christus-Sol, driving a sun-chariot in direct imitation of the god Apollo. A fourth-century marble statue now in the Vatican Museums reimagines Christ as the Good Shepherd, borrowing its entire composition from common Roman pastoral figures.

The final step in this European evolution came with the need for an image of imperial authority following Constantine’s conversion. Artists synthesized the commanding beard and throne of Zeus with the thoughtful countenance of a Greek philosopher to create the Christ Pantocrator, or "Ruler of All." This powerful type reached its definitive form in the sixth-century encaustic icon preserved at Saint Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai, an image that would be exported globally as the orthodox face of God.

Ancient African Christian Traditions

While this European tradition was consolidating, however, equally ancient and vibrant Christian cultures in Africa were creating their own visual languages. The Nubian kingdoms of Nobatia, Makuria, and Alodia, located in modern-day Sudan, constructed great cathedrals whose walls were covered in frescoes. A painting from the eighth or ninth century, discovered in the Cathedral of Faras and now housed in Warsaw, shows the Virgin Mary with distinctly Nubian facial features.

Meanwhile, the Ethiopian Empire fostered an unbroken Christian artistic tradition entirely separate from European influence. Its most stunning architectural achievement remains the eleven rock-hewn churches of Lalibela, carved downward from solid volcanic rock in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

Bete Georgis (St. George), the last church built by King Lalibela and the most famous of all the rock-hewn churches.

Ethiopian illuminators, working on texts like the Garima Gospels—which are among the oldest surviving illuminated Christian manuscripts anywhere—consistently depicted Christ, Mary, and the saints with dark skin, broad noses, and tightly curled hair. A fifteenth-century triptych showing the Life of Christ, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, demonstrates the persistence of this African representation for over a millennium.

Faith Under Oppression

The transatlantic slave trade violently disrupted these traditions, imposing the European image of a white Christ while using scripture to justify bondage. Confronted with this weaponized theology, enslaved Africans in the Americas engineered a brilliant covert response. Denied access to canvas or chisel, they wove a new theology of liberation into their music and oral culture. Spirituals like "Wade in the Water," with its coded references to baptism and escape, or "Didn't My Lord Deliver Daniel," which framed their hope for freedom within biblical precedent, functioned as the Sator Squares of their era—a hidden language of faith and resistance.

Reclaiming Sacred Imagery

The eventual emancipation of Black people and the cultural movements of the twentieth century enabled a shift from this coded symbolism to an overt reclamation of visual space. Artists of the Harlem Renaissance and the Civil Rights era began directly challenging the European hegemony over sacred imagery. Vincent D. Smith’s 1968 print series, The Passion, transposed the narrative of Christ’s suffering onto the stark realities of Black urban life. In his murals, such as the one created for the Blue Triangle YWCA in Houston, John Biggers integrated a majestic, dark-skinned Christ-figure with the forms and symbols of West African art, like the nkisi nkondi power figure.

“Jesus of the People” (1999), by Janet McKenzie.

This reclamation continues to evolve within the contemporary art world. Janet McKenzie’s "Jesus of the People," which won a National Catholic Reporter competition, presents an androgynous Black Christ. Also, the installation of "Christ in the Wilderness", a statue by artist Margaret Adams at the Washington National Cathedral in 2014 signals an institutional recognition of this long-standing theological and artistic correction.

A Complex and Ongoing History

The complete history of Christ’s image is therefore not a single, linear narrative but a complex and often contested dialogue across cultures and centuries. The visual legacy of Africa, from the ancient frescoes of Nubia and the illuminated manuscripts of Ethiopia to the spirituals of the plantation and the powerful murals of the modern era, forms a continuous and theologically serious counter-narrative.

This work does not represent a departure from Christian tradition but a fulfillment of its most ancient impulse—the deeply human need to find one’s own face in the face of God, a practice as old as the faith itself.