The Eternal Dialogue: Art's Quiet Pursuit of the Sacred

“Untitled“ by Frank Kelly, Jr. whose artwork explores symbolism and spirituality through color, form, and texture.

When we think of religion in art, our minds often jump to the grand altarpieces of the Renaissance—a luminous Madonna, a suffering Christ, scenes from scripture designed to inspire devotion. These works are the overture, a direct and powerful conversation between faith and art.

But this dialogue is far from confined to European cathedrals. Here at the Northeast Louisiana Delta African-American Heritage Museum, we see the same spiritual thread woven into African-American artistic traditions—from the coded symbols in quilts to the transcendent rhythms of gospel music made visual. This reveals a profound truth: the pursuit of the sacred through art is a universal human impulse, one that transcends geography and creed. Even after the decline of any single institution as art’s patron, that quieter spiritual thread endures, guiding artists toward the ineffable questions of transcendence, meaning, and the sublime.

The Renaissance: The Divine in the Human

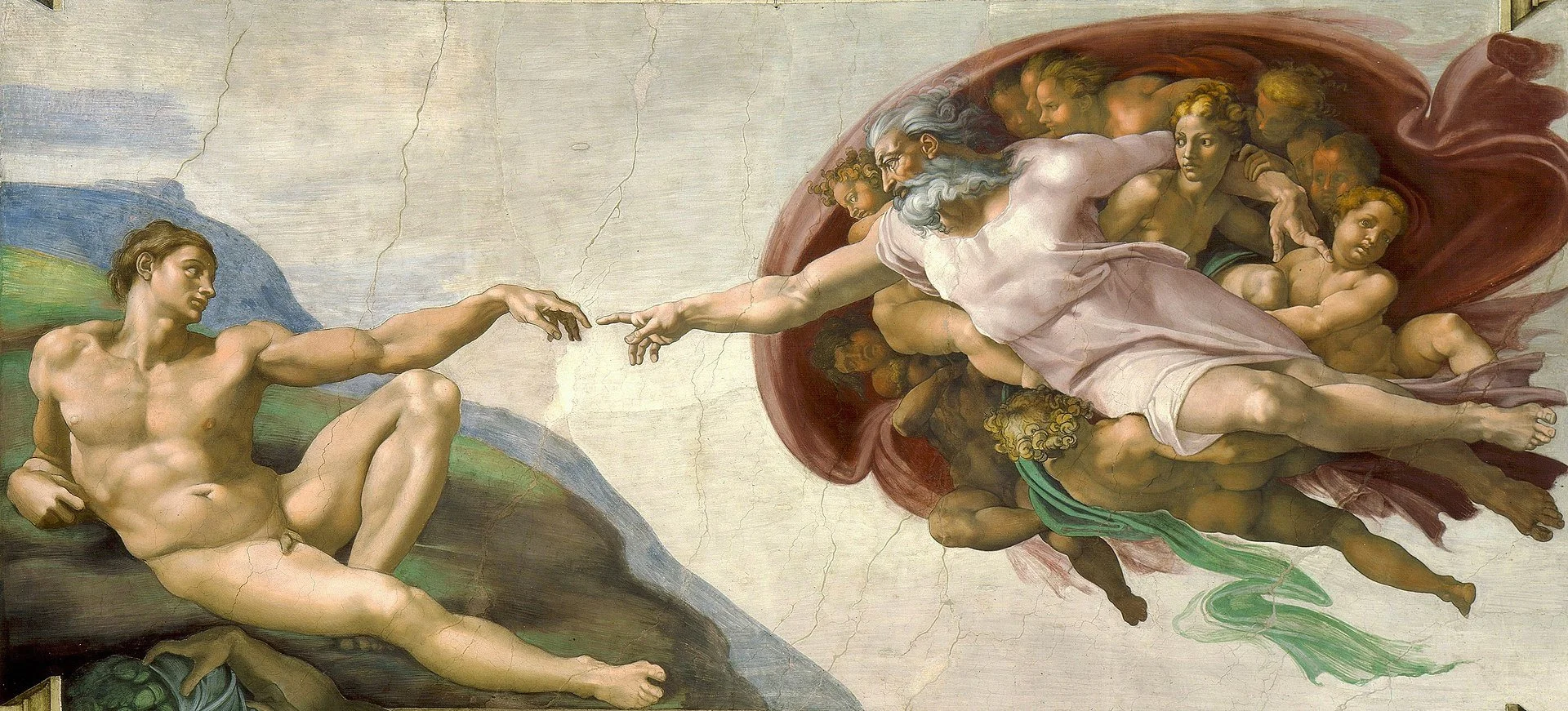

Michelangelo - Creation of Adam, Sistine Chapel (detail).

In the Renaissance, the "what" was almost always a biblical narrative. But the "why" was often deeper. Artists used religious subjects as a vessel for a burgeoning humanist inquiry. Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling, for instance, is not just a depiction of a Bible story; it’s a profound meditation on the spark of consciousness. The sacred form became a vehicle to explore emotion and humanity’s place in the cosmos—a theme that resonates with the exploration of identity, resilience, and transcendence found throughout African-American art.

The Modern Turn: Spirituality as Abstraction

As the 20th century dawned, the spiritual quest in art transformed. Artists began to shed the figure, seeking a visual language for the spiritual that was free from doctrine.

Wassily Kandinsky, Composition VII, an abstract exploration of spiritual resonance.

Wassily Kandinsky believed art must function like music, speaking directly to the soul. His vibrant, chaotic compositions are attempts to visualize the cosmic and the ecstatic. He wasn't painting God; he was painting God’s frequency—a concept not unlike the way a gospel choir uses harmony and rhythm to reach past words toward pure feeling.

Hilma af Klint went a step further, claiming her groundbreaking abstract forms were directly channeled from a higher spiritual reality. For af Klint, abstraction wasn’t a stylistic choice; it was a medium for revelation. This spirit-led approach to creation finds a powerful parallel in the visionary, often improvisational traditions of the Black Atlantic, where art becomes a conduit for something greater than the self.

Here in the Delta, artists like Frank Kelly, Jr. explore this same terrain. His works, infused with symbolism and resilience, show how abstraction and spirituality can meet to reveal layers of meaning that go far beyond the canvas.

The Contemporary Dialogue: Memory, Myth, and Material

Today’s artists continue this dialogue, often grappling with the ruins of old beliefs and the search for new ones.

Anselm Kiefer confronts the weight of history, weaving together mythology and Jewish mysticism. His monumental, ash-laden works are archaeological digs into the soul, asking how meaning can be forged from the rubble of history. This resonates with the work of African-American artists like Betye Saar, whose assemblages draw on ritual, memory, and mysticism to reclaim history and explore spiritual identity.

For many contemporary artists, the sacred emerges in the elevation of the everyday. The obsessive, almost devotional act of rendering an object, as seen in CJ Hendry’s hyper-realistic drawings, comments on modern idolatry. Similarly, Kerry James Marshall imbues scenes of ordinary Black life with a monumental, sacred quality, highlighting the dignity and spiritual depth found within the community.

“Untitled“ by Daryl Triplett who touches on spirituality through historical imagery and contemporary lived experience.

Closer to home, Daryl Triplett’s paintings echo this pursuit by drawing from contemporary themes and lived experience in the Delta. His work shows how faith, memory, and history remain inseparable—reminding us that spirituality is not only a matter of doctrine but of survival, heritage, and community resilience.

Why Does This Relationship Persist? A Mission Close to Home

So, why is this link between art and the sacred so stubbornly prevalent? It stems from a shared drive to confront the sublime, to ask the big questions of life and death, and to perform the alchemy of transforming base materials into meaning.

Part of our mission at the Northeast Louisiana Delta African-American Heritage Museum is to preserve and share how the artists of our region express these very spiritual currents. Whether overtly or subtly, this eternal dialogue between the material and the spiritual is alive here—in the stories our art tells, the history it holds, and the community it builds. It is a dialogue that continues to inspire new generations, reminding us that the desire to connect with something beyond ourselves is at the heart of both art and humanity.

We’d love to hear your thoughts—and we invite you to experience this dialogue firsthand here at the museum, where art continues to carry the sacred into our shared present.

Where have you unexpectedly felt a sense of the sacred or sublime—whether in a work of art, a piece of music, or right here in our community?