Etched in Clay: The Legacy of David Drake, Potter and Poet

David Drake (ca. 1801–1870s). Stony Bluff Manufactory (Edgefield District, South Carolina). Storage jar, 1858.

In the heart of 19th-century South Carolina, where enslaved people were systematically dehumanized, David Drake—known to history as Dave the Potter—defied erasure. With each jar he shaped and each word he inscribed, Dave asserted his identity, leaving behind a legacy that transcends time.

A Potter’s Journey

Born around 1801 in the Edgefield District of South Carolina, Dave lived most of his life enslaved. He was first owned by Harvey Drake, a prominent figure in the region’s thriving pottery industry. Later, he was enslaved by Lewis Miles, whose kiln yard may have allowed Dave greater creative freedom. It was likely during this later period that Dave’s distinctive voice—both literal and artistic—began to emerge most clearly.

Despite South Carolina’s harsh laws forbidding enslaved people from becoming literate, Dave somehow learned to read and write. This alone was extraordinary. Yet what makes his story singular in American history is that he used that literacy—openly, even defiantly—by inscribing poetry onto the very jars he was enslaved to make.

Artistry in Stoneware

Dave created large alkaline-glazed stoneware jars, often ranging from 20 to 40 gallons in size. This glaze, made from local clay and wood ash, was a regional innovation—fired at high temperatures to produce durable, water-tight vessels. Though utilitarian in function, Dave’s jars became vessels for his thoughts, reflections, and wit.

Scholars estimate he produced tens of thousands of pots, though only about 100 signed examples survive. His poetic inscriptions range from philosophical to playful, often paired with measurements or references to the jar’s contents:

"I wonder where is all my relations

Friendship to all—and every nation."

—August 16, 1857

"A very large jar which has 4 handles

Pack it full of fresh meat—then light candles."

Dave’s work was not merely functional; it was subversive. In a society that denied his humanity, his jars—marked with his name, his poetry, and his thoughts—became acts of resistance.

A Lasting Impact

This jar contains the verse “I made this jar all of cross. If you don’t repent, you will be lost”. Inscribed May 3, 1862.

Today, Dave’s pottery is housed in some of the most prestigious art institutions in the country. These pieces serve not only as examples of masterful craftsmanship but also as enduring documents of literacy, labor, and creative defiance during slavery.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Accession No. 2022.65): Features a monumental jar inscribed with a poem and the name of Lewis Miles.

The Smithsonian National Museum of American History: Holds a large jar dated 1862, attributed to Dave and representative of his later work.

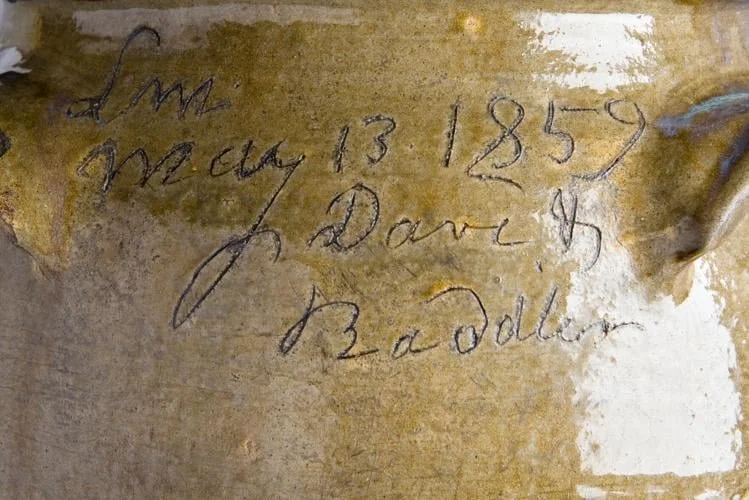

Philadelphia Museum of Art: Preserves a jar from 1859 inscribed with a biblical passage—one of the rarest surviving examples of literacy under slavery.

Continuing the Conversation

Dave’s story has been reexamined through exhibitions like Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina (2022–2023), which debuted at The Met and traveled to institutions including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and the Milwaukee Art Museum. These efforts spotlight the creative agency of Black artisans in the antebellum South—long overlooked in traditional art history.

Today, contemporary artists, scholars, and educators continue to draw inspiration from Dave’s life—his craftsmanship, his courage, and his ability to speak through clay across centuries. His story challenges us to see the intersections of art, labor, and resistance.