Black Figures in Western Religious Art

For nearly a thousand years, Western religious art has presented a striking falsehood: biblical figures—Middle Eastern in origin—portrayed as white Europeans. This wasn’t artistic accident. It was the product of theology, politics, and racial ideology working together to reframe the sacred.

Theology and the Whitening of the Sacred

In the Middle Ages, scholars misread the story of Noah’s sons in Genesis to divide humanity into three “races” — Semitic (Asian), Japhetic (European), and Hamitic (African), the last tied to servitude. By the 12th century, cathedral windows and illustrated manuscripts reflected this hierarchy, linking holiness to European features.

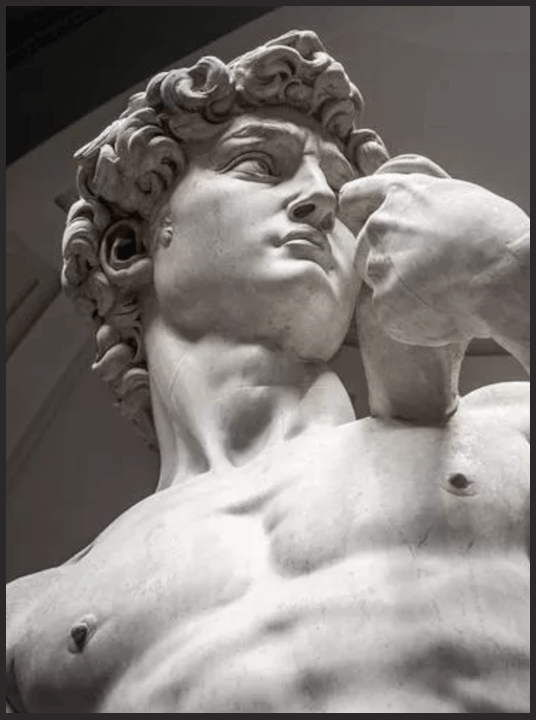

Renaissance humanists doubled down. Neo-Platonists like Marsilio Ficino equated divine radiance with luminous whiteness (claritas), a hierarchy Renaissance artists applied to human figures. His De Amore (1484) deemed gold and snow the pinnacle of chromatic purity—a standard that, when applied to sacred art, implicitly marginalized darker pigmentation, a framework that justified Michelangelo’s David as a pale Florentine youth and Raphael’s Sistine Madonna as the blue-eyed standard of purity.

Raphael, Sistine Madonna, c. 1512–1513, oil on canvas, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, David, 1501–1504, marble, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy.

Limited Inclusion, Carefully Controlled

When Black figures did appear, their roles were narrow. The Ethiopian eunuch in Acts, Christianity’s first recorded Black convert, was almost always shown kneeling before white apostles. Saint Maurice, an Egyptian soldier-saint, was gradually lightened in European art, until Lucas Cranach’s 16th-century version rendered him nearly indistinguishable from his comrades.

Even celebrated inclusions like the Black Magus, Balthazar, were often erased. Technical imaging has revealed that some early Black depictions were later overpainted, as with the Norton Simon Museum’s Portrait of a Moor, misidentified for centuries.

Jan Mostaert, Portrait of a Moor, c. 1525–1530, oil on oak panel.

Georges Trubert, The Adoration of the Magi, from a Book of Hours (text in Latin), Provence, France, c. 1480–1490. The J. Paul Getty Museum.

What Scholarship Is Recovering

Counter-narratives remain. The Black Madonna of Montserrat, venerated in Catalonia since 880 AD, retains African features despite centuries of attempts at “Europeanization.” Conservation work on Coptic icons in Egypt shows pigments intentionally lightened during 18th-century “restorations.”

The stakes are theological as well as artistic. Historian Christy Clark-Pujara has shown how, in colonial Louisiana, images of a porcelain-skinned Virgin were used to justify the enslavement of Black Catholics. Theologian James Cone called this fusion of whiteness and divinity “a spiritual apartheid.”

Why This Matters

Images are not neutral. They teach us who belongs in the sacred story—and who doesn’t. When Black figures are absent from religious art, it’s not just history that’s erased, but a vital mirror for communities of faith.

As a heritage museum, our role is not to conserve these works physically, but to share them—to communicate the patterns of inclusion and exclusion that shaped them, and to connect those histories to the present. Because sometimes the most sacred act is not creating a new image, but understanding the old one.