Faith and Power: The African Presence in Renaissance Religious Art

Detail of Black King Balthazar from "The Adoration of the Kings" by Jan Gossaert, (ca. 1510–1515).

When we think of the Renaissance, Black figures aren’t always the first to come to mind. Yet from European churches to the royal courts of the Kingdom of Kongo, the presence of Africans in religious art tells a story of faith, resilience, and cultural exchange that still echoes today. These images—whether painted on chapel walls in Flanders or carved in ivory in Central Africa—offer glimpses into a deeply interconnected world and a long history of Black spiritual imagination.

A Hidden Presence in Sacred Art

In the religious paintings of Renaissance Europe, Africans often appear at the edges of the sacred scene. The most familiar example is Balthazar, the African king among the Magi in the Adoration of the Magi, rendered in fine robes, bearing gifts for the Christ child. Elsewhere, Black figures can be found as saints, angels, or attendants—present, if not always centered. These portrayals reflect both Europe’s growing awareness of Africa and its tendency to project exoticized or idealized visions onto Black subjects.

"The Adoration of the Magi" by Hieronymus Bosch, (c. 1494).

These images mirrored a social reality: Africans were living and working in Europe during the Renaissance. In cities like Lisbon, Seville, Venice, and Antwerp, Black individuals—some enslaved, others free—were part of daily life. They served in noble households, navigated port economies, and at times rose to prominence in court or religious life. While historical records are fragmentary, their presence in art hints at lives lived with complexity and, at times, considerable influence.

A Life Beyond the Canvas

But Africans were not only the subjects of someone else’s brush—they were also creators, interpreters, and cultural innovators in their own right. Nowhere is this clearer than in the Kingdom of Kongo. In the late 15th century, Kongo rulers initiated contact with the Portuguese, not as passive recipients of European influence but as strategic partners seeking to expand their spiritual and political reach. King Nzinga a Nkuwu’s baptism in 1491 (as João I) marked the beginning of a remarkable era in which Christianity was absorbed, reshaped, and made Kongo.

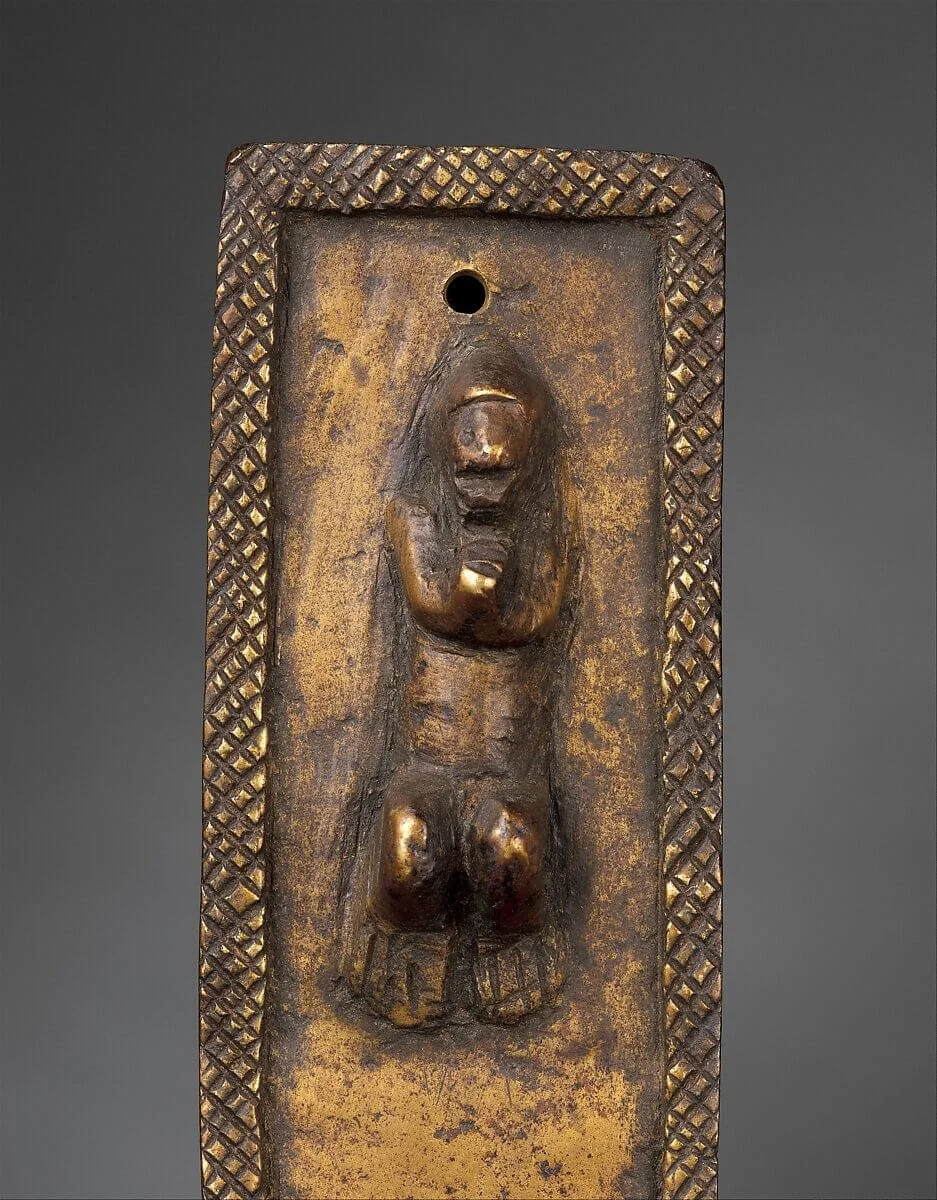

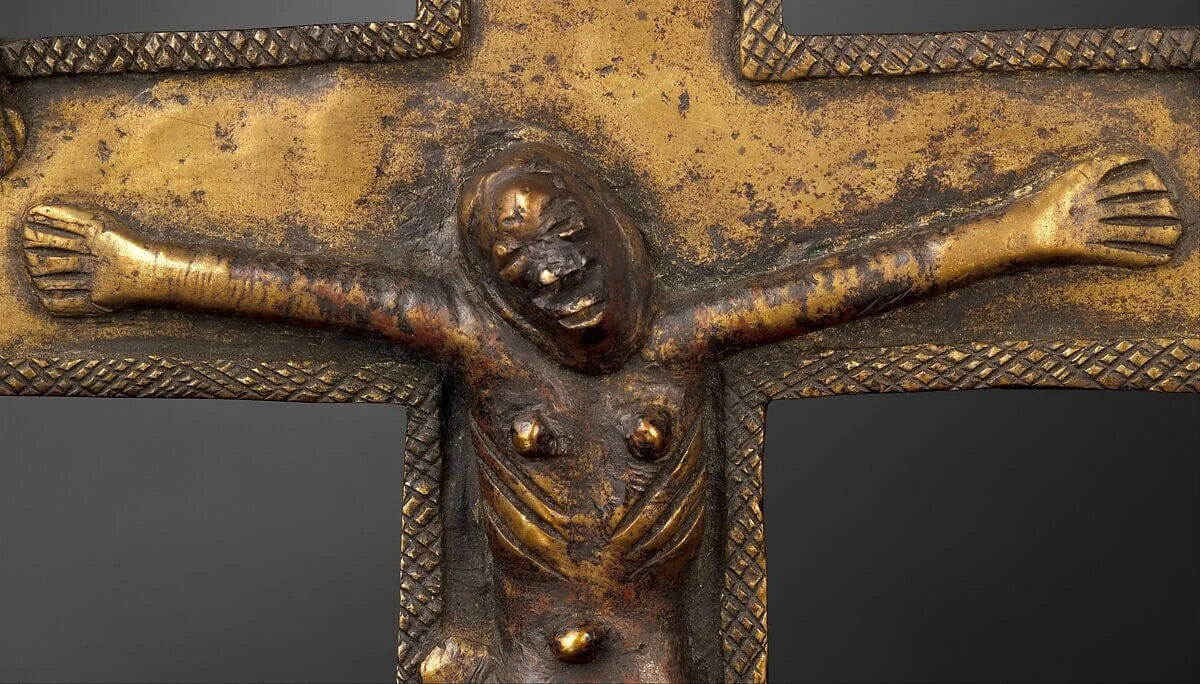

Kongo artists began producing Christian devotional objects that bore the stamp of local aesthetics and belief. Wooden and ivory crucifixes often depicted Christ with African features or incorporated cosmological symbols unique to the region.

Crucifix, 16th–17th century. Kongo artist. Solid cast brass. Democratic Republic of the Congo; Angola; Republic of the Congo.

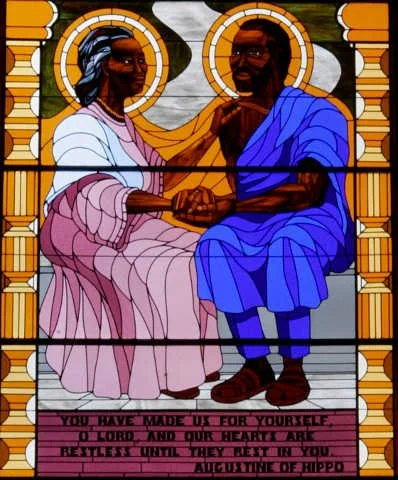

What emerged was not a mere imitation of European religious art, but a powerful act of visual theology—an African Christianity articulated through African hands. Women also played a role in shaping this tradition, both as patrons and transmitters of belief within the community. Likewise, in Europe, some religious artworks—like depictions of St. Monica (the African mother of St. Augustine) or the Black Madonnas venerated across Italy, France, and Spain—point to an enduring if complicated reverence for African women in sacred contexts.

St. Augustine and his mother, St. Monica, are depicted in a stained-glass window at St. Augustine Church in Washington.

The Spirit Lives On

This act of creative adaptation resonates across time. Centuries later, African-descended peoples in the Americas would also blend Christian symbols with older spiritual practices, giving rise to the richly syncretic traditions of African-American faith. From the carved gravestones in early Black churches to the stained-glass windows depicting Black saints, religious art has remained a vital language of survival, transformation, and praise.

At a time when the global history of art is being reexamined, these stories urge us to look again—at the margins of famous paintings, at the craftsmanship of distant kingdoms, and at the quiet power of belief carried across oceans. African contributions to religious art are not footnotes. They are foundational.

At the Northeast Louisiana Delta African-American Heritage Museum, we remain interested in legacies that connect the past to the present—inviting us to see ourselves in the story of faith, creativity, and endurance. What hidden connections will we discover next?